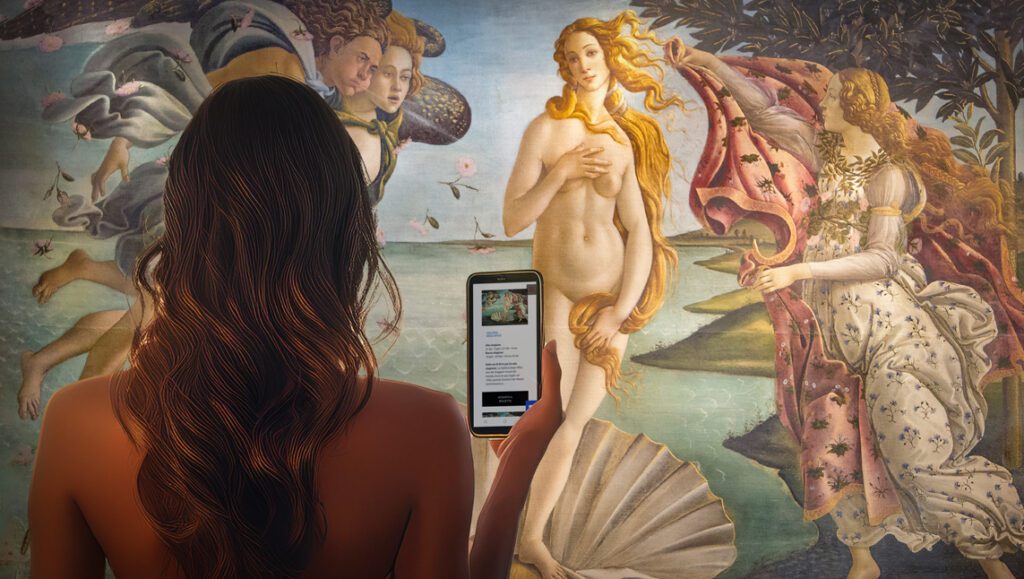

The ‘Palazzo Pubblico’ of Siena

The ‘Palazzo Pubblico’ is one of the most important buildings to be admired in Siena and deserves to be properly discovered thanks to a guided tour of the city.

Just to understand why this edifice is so important, it will suffice to mention some of the most beautiful works that are preserved in the building that houses the Civic Museum. If we visit Palazzo Pubblico of Siena, we can find the cycle of Good and Bad Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti that is definitely one of the most dramatic profane themed cycles preserved in Italy, or the stories of heroes of ancient Rome painted by the famous Sienese artist Domenico Beccafumi.

Alongside these masterpieces, there is another one that will take your breath away for its beauty: it’s the ‘Maestà’ (Majesty), painted by Simone Martini in the so-called Sala del Mappamondo and which in 2015 celebrated the seven hundredth anniversary of its execution.

Maestà, Simone Martini, 1315-20, Sala del Mappamondo, Palazzo Pubblico, Sien

The first important ‘Maestà’, after that of Duccio

The large fresco of Palazzo Pubblico, visible visiting the museum, was carried out four years after the first Maestà, the “sacred one” created by Duccio di Buoninsegna for the Duomo. Beyond the differences of context of the two Sienese paintings, the Simone Martini’s “has lost all its sacred character, in favour of secular and courteous traits, created by that great tournament pavilion under which the scene takes place” ¹.

The Lady, however, is not waiting for her knight at the tournament, but presides over the meetings of the Republic of Siena’s Council which were held in this room. The Virgin dresses sumptuous garments, decorated with embroideries in gold and precious stones, elements that are not simply painted in the fresco but were made in relief thanks to the insertion of coloured stones inside the wall.

The expedient of inserting elements into the surface was typical of Simone Martini’s manner and also demonstrates the painter’s familiarity with the techniques of jewellery, an art that, rather than sculpture or painting, had a certain renown in Siena in the early fourteenth century. At that time, generations of city’s artists had been called to work as goldsmiths for the most important courts of Europe, as happened to Pace di Valentino, author of the very precious Reliquary of San Galgano, or Guccio di Mannaia. An instrument that Simone Martini well knew was the punch, particularly used in jewellery to make seals and medals. As confirmation of it, Simone Martini reproduced a series of painted medals all around the fresco of the ‘Maestà’.

A literate painter

In addition to his technical skills as a painter and goldsmith, Simone also demonstrated his literature’s knowledge in the work, specifically of the Stilnovo poetry, given that the artist, or whoever it is for, placed a series of poetic captions inside the painting where he develops a dialogue, with a series of questions and answers between the rulers and the Virgin. Although the context painted by the artist is courteous, the verses are here written in the vernacular. We are in a historical moment where the language is being vulgarised. As already done for the Siena Municipality Constitution, which was written between 1309-10 using the vernacular, the need for an immediate communication that avoids the formalities of the Latin language. The Virgin turns to the rulers of the city – who are not members of the aristocratic class but bourgeois, belonging to the middle class – and uses their own language, transmitting to them messages in which the civic values of unity are emphasised, a kind of theme that was so dear to the Government at that time.

Discover the dedicated tour for the visit of the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena ⟢