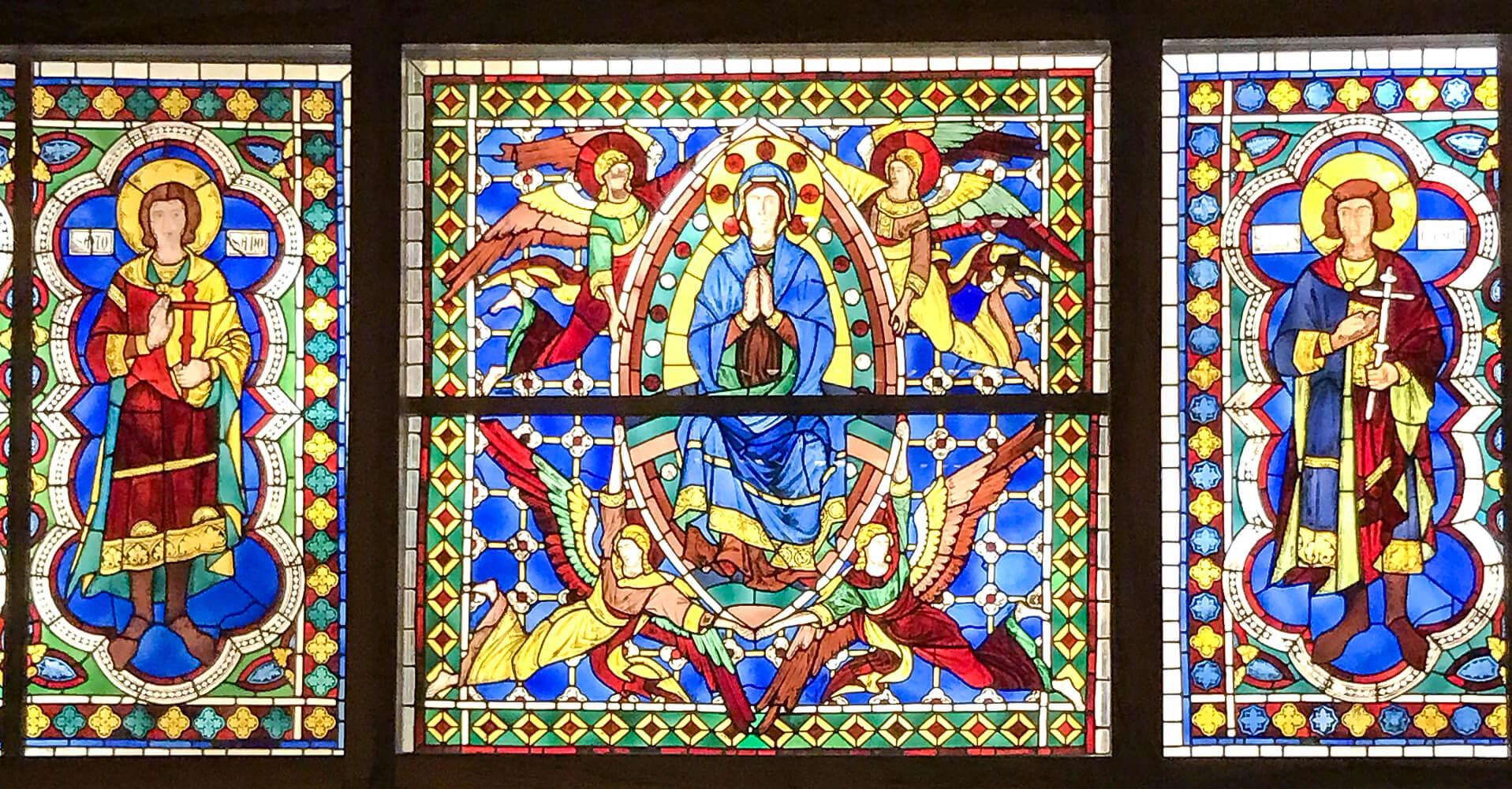

The stained glass window of the Cathedral of Siena, the almost unknown marvel

The stained glass window of the Cathedral of Siena is a masterpiece that goes almost completely unnoticed by the attention of visitors who, already dazzled by the many wonders of the Sienese cathedral, arrive at the end of the itinerary almost addicted to the many beauties.

It actually happens that no one knows that the window that closes the so-called “eye of the Cathedral”, a brightly colored luminous point, is one of the oldest works in the whole church: it dates back to the years 1287-1289, at the time the great painter Duccio di Buoninsegna made the drawings for the scenes of this large window, which were then translated by expert master glassmakers into the masterpiece that can be appreciated today.

The scenes represented in the stained glass window of the Cathedral of Siena are those of the Transit of the Virgin, that is to say, the last important moments of Mary’s life on earth and which enjoyed great iconographic success at the end of the Middle Ages; the culminating moment of the series of Marian episodes is the coronation of the Virgin, a scene that we also find represented in the Sienese window.

The reasons to admire a masterpiece

But what is it that allows us to say that this stained glass window is considered a masterpiece? What would be the reasons to make it feel so important?

Well, already starting from its antiquity, the very fact of being almost eight centuries old makes it first of all a work out of the ordinary. Then, since it is so ancient, it is one of the first works to be found in the Duomo and, above all, a ‘colour’ work in a context that originally where the environment of the Duomo was essentially characterized by black-and-white two-tone where few other elements had a polychromy (eg the altarpieces and the pulpit by Nicola Pisano).

Therefore, its being ancient certainly made it a work that once stood out much more than today in which the Cathedral is clogged with many coloured works.

Speaking then in properly technical terms, the stained glass window is a remarkable work also considering its size. Although not something much perceived from floor level, its diameter is a good six meters, making it one of the largest stained glass windows in the entire history of art. The window of the Cathedral of Siena is divided into five squares and four corners; the three squares of the vertical band represent the final episodes of the Stories of the Virgin which were elaborated in the medieval tradition, in particular from the written edition of the Golden Legend by the Dominican friar Jacopo da Varaze and which are the Dormitio, the Assumption into heaven and the ‘Coronation of the Virgin.

An iconography from the French tradition

However, if the stories of the transit, reproduced in the stained glass window, are inspired by the literary work of Jacopo da Varaze, the image of the assumption, as underlined by Roberto Guerrini, derives from the French Mariological tradition, particularly in the sculptural cycles of the great cathedrals such as in Chartres and Paris.

In that context, starting from the 12th century, the writings of the Cistercian monk and theologian Bernardo di Chiaravalle had had great importance, who had firmly promoted the concept of the assumption of the Madonna body and soul into heaven.

Returning to the stained glass window of the Cathedral of Siena, let’s see the other reasons for considering this work an authentic masterpiece. If the development of the Mariological theme of transit has its roots in the French theological tradition, it is of further interest that Duccio drew inspiration for the drawing from the pictorial tradition of his time, looking in particular at the lesson of his master Cimabue.

In this regard it should be remembered that, almost in the same years of the Sienese stained glass window, the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi was decorated in the apse walls with a cycle of paintings with the Stories of the Virgin by Cimabue himself and that shortly before the walls and the windows of the Franciscan church were decorated by ‘Oltremontani’ masters whose style left a deep imprint on the ‘Italian’ artists of the following generations: Duccio himself was not irrelevant to Gothic elegance, as he will clearly demonstrate in many of his works, such as in the famous Rucellai Madonna and in the subsequent Maestà always for the Sienese Cathedral.

Coronation of the Virgin, stained glass window, Duccio di Buoninsegna, Siena Cathedral

Christ and the Virgin inthroned, Cimabue, Basilica superiore di Assisi (Foto www.gliscritti.it Wikimedia Commons)

The Duccesque stained glass window and Cimabue’s paintings in Assisi

By comparing the Marian stories of Assisi and those of Siena, it is clear that Duccio had looked at the paintings of his master in Assisi: the throne of the Coronation in the Sienese glass recalls that of Assisi (FIG 2), as can be seen in the pose front of the backrest and in the same decoration with octagon motif. However, the Sienese painter shows ‘insecurities’ in the perspective rendering of the throne, where the frontal representation of Christ, the Virgin and the backrest do not find coherence with the armrests and the suppedaneum (FIG 3), still represented sideways, according to what it was a traditional pattern in painting.

These hesitations are also found in the scene of the first panel with the Burial of the Virgin, where, as Luciano Bellosi pointed, the rear side of the sepulcher assumes a position that will never allow it to rejoin one of the side walls of the sepulcher.

However, the insecurities in the ‘spatial’ research cannot be pointed to Duccio’s inability to innovate, rather to the figurative culture of the artists of the time, made up of experiments and ‘perspective’ daring that will reach a level of formal coherence only with Giotto.

Master of Cabestany (attr.), Virgin Assumpted, capital Rieux Minervois Church, France (Ph: Wikimedia Commons)

In Assisi the Assumption is rendered by Cimabue as a reunion with Christ, with the two figures sitting on the band/seat; likewise, the mandorla is made habitable in Siena by Duccio, with Maria then sitting on the wing; however, the Sienese Virgin is depicted frontally, according to an approach that we find in all the previous figurative tradition, especially in the miniature.

Mary’s feet are placed on staggered levels in the window, thus creating a depression in the part of the mantle which generates a chiaroscuro play, skilfully modulated by the glass maker, which suggests the depth of the figure.

If until now the reasons hadn’t been enough to properly appreciate this masterpiece, there is the beauty of the aesthetic contemplation of this stained glass window, which has truly beautiful colours:

the blue mantle and the wine-coloured robe have folds that give dynamism to the contours of the Virgin; moreover, the mantle also falls on the plane of the seat: this suggests a space behind the figure, at the same time giving a plastic consistency to the Virgin emerging from the mandorla/throne.

There are therefore several factors that give dynamism to the scenes in the stained glass window of the Cathedral; the sense of innovation is contrasted by Mary’s solemn and hieratic pose, according to the scheme of the previous iconographic tradition.

According to the observations made by Roberto Guerrini in an essay, the indirect precedents of this formula could be identified in the French sculpture of the XII century, with particular reference to the works of the anonymous Master of Cabestany (FIG 5) which are located in the homonymous locality in the South of the French Pyrenees and who is an artist already attested in the Siena area with the famous capital of the Abbey of Sant’Antimo.

Once again therefore the source, not only theological but also iconographic, of the Virgin of the Assumption, presented inside a mandorla, like the Christ of the Parusia (a recurring motif in the representations of the Final Judgment) would be French.

However, it is quite well known that Italian artists, especially those from Siena, were particularly sensitive to the stylistic and figurative innovations that came from France and that circulated in the Italian territory through miniatures, ivory sculptures, goldsmith objects and notebooks.

After the series of reasons listed for admiring the stained glass window of the Cathedral of Siena, the last and perhaps most convincing remains: it is rather uncomfortable and almost impossible to appreciate the details of the glass – due to the distance between the vault of the apse and the walking surface -, the good news to know is that the one present in the Cathedral today is not the original stained glass window, but only the copy; instead, it is possible to see the original stained glass window and be able to admire it in all its splendour of colours and down to the smallest details inside the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, where the artefact is displayed at eye level ⟢

Bibliography

1] A.Bagnoli, R.Bartalini, L.Bellosi, M.Laclotte (a cura di), Duccio, alle origini della pittura senese, Catalogue of the exhibition , Silvana Editoriale, Milano, 2003, pp.166-180 (Italian edition);

2] Marilena Caciorgna, Roberto Guerrini, Alma Sena : percorsi iconografici nell’arte e nella cultura senese: assunta, buon governo, credo, virtu e fortuna, biografia dipinta, Monte dei Paschi di Siena Gruppo MPS, Siena, 2007, p.12 (Italian edition);