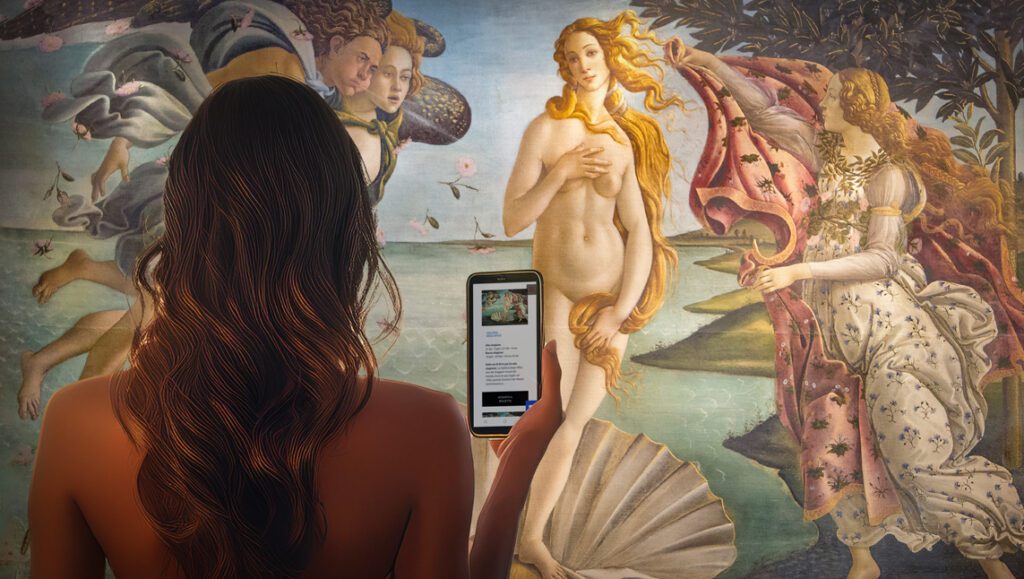

The Primavera by Botticelli, one of the most admired paintings in the Uffizi

A visit to the Uffizi Gallery cannot be set aside from one of the most celebrated works of the Italian Renaissance: the Primavera, painted by Botticelli.

This painting, one of the most admired and photographed in the museum, catches the attention for the beauty and elegance of the figures represented by Sandro Botticelli in what was his typical manner in the late seventies of the fifteenth century – the period to which the painting is traced Florentine – when the artist tended to represent the figures in an idealized way. For the graceful elegance and solemn gait of the figures, the Primavera by Botticelli is a true icon of the Uffizi, a simulacrum destination of incessant tourist pilgrimages that every day fill what is a great sanctuary of painting.

The reasons why many people remain completely enraptured by the beauty of the Primavera painted by Botticelli lies both in the undoubted charm of the work and in the fact that an air of mystery envelops the silhouettes of these figures that seem like dancing in an airtight garden, a hortus conclusus that contains many mysteries.

The hidden plants and flowers of the painting

When one talks about thePrimavera by Botticelli it’s almost exclusively seen the figures that make up the painting, without ever going to analyse the plant elements that have been reproduced by great accuracy by the Florentine painter. Leaving aside the Primavera plants’ symbolism is definitely compromising to interpret its own iconography.

Just to get an idea of how much importance has been given by the artist to plant species, it is appropriate to remember their considerable number: forty-six are the plant species that have been identified and described – thanks to the collaboration of experts from the Erbario Centrale at the University of Florence – and the number of times these repeat in the painting is over two hundred. An immense and varied plant world therefore remains unknown and neglected by most visitors, with the result that many of the symbols and references to which the plants represented refer are lost.

It has been estimated Botticelli’s Primavera is photographed two thousand times a day

The Primavera as a wedding gift?

Before starting a brief excursus to identify some of the plant species reproduced on the painting, it is worth remembering that one of the interpretations given to Botticelli’s Primavera as a whole wants this to have been commissioned by Lorenzo the Magnificent as a wedding gift for his cousin – Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco – who contracted marriage with Semiramide Appiani on 19 July 1482.

Beyond the reliability of this interpretation, it is important to take this fact into account when it is analyzed the fascinating symbolism of some plants painted by Botticelli, a series of pictures that seems to be related to wedding sphere.

Among the species, for example there is the cornflower, a plant Botticelli represented on the robe and in the hair of the figure that the critic identifies as Flora (the third in order of appearance from right to left) goddess of nature and character that has symbolic references both to the client family of the painting – that of the Medici – and to Florence itself as it regards the foundation of the city at the ancient Roman’s time…

Plants blooming in May

The cornflower plant also appears in other swaths of the painting and it is linked to the other figures featured in this hermetic scene; it is worth mentioning here the fact that the plant blooms in May is certainly not secondary if it is taken into account this must have been the month in which the young couple Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco – Semiramide Appiani would marry; in the end, this did not happen as the marriage was postponed due to a nefarious event that affected the Medici family …

Detail of the figures of Flora (to the left) and Chloris while she’s grabbed by Zephyrus (to the right)

Curious plants …

Among the plants present in the Primavera painted by Botticelli also there is strawberry. Just like cornflower, strawberries also bear fruit in May and could have a connection with the theme of marriage, since strawberries traditionally allude to seduction and sensual pleasure: no matter how much you eat this fruit because you will never be full on it. But it is not only a popular tradition that binds strawberry plant to seduction since there are several references that can be found in literature, as does Sassoferrato who, in its Ballate apocrife – a work erroneously attributed to Agnolo Poliziano –, the lips of the poet’s beloved are compared to rubies and strawberries¹.

The branch coming out from Chloris’ mouth

If sometimes in the Primavera the plants painted by Botticelli appear painted down to the smallest detail to be difficultly located, the plant that comes out from Chloris’ mouth – the second figure looking at the painting always from right to left – does not go unnoticed, This plant, which comes out from the nymph’s mouth, is one of the most striking elements of the entire composition; in reality, it is not a single plant but a series of different plants including the strawberry; the latter then reappears both in Flora’s hair and in the lawn before Venus – the goddess of love.

Detail of Flora‘s feet and of the plants painted by Botticelli on the meadow around the figure

The hyacinth sprinkled on the wedding bed

By continuing to read the picture from right to left, it’s possible to see how Flora was represented in the act of distributing flowers on the lawn in front of her; although it may seem that, with this gesture, Botticelli almost wanted to capture the goddess in a completely spontaneous and natural attitude, I think it is particularly suggestive to think that, even in this case, the painter would refer to a literary work, according to what – at least – can be read in a passage from De Amore Coniugali in which Gioviano Pontano speaks about Hymen – the Greek god of marriage – who sprinkled his wedding bed with hyacinth flowers². It will also be useful to remember here that the Imeneo, an ancient Greek text that dealt with Hymen’s deeds, was a text read on the occasion of the celebration of weddings until Roman times. Could this be another reference to Pierfrancesco de Medici’s wedding? It cannot be said with certainty, however a hyacinth plant has been identified in the Uffizi painting right next to the left foot of the figure of Flora …

Detail of the figures of the Three Graces

The role of the Graces

That Hyacinth had an important symbolism can also be seen for its connection with the Graces of which Botticelli endowed a magnificent representation on the left side of the Primavera. The great Italian poet Torquato Tasso would write that the hyacinth was a plant brought by the Graces³.

It is possible that Botticelli and Poliziano already knew the ancient source from which Torquato Tasso would resume the description of the hyacinth brought from the Graces. This is demonstrated by the fact the plant appears near the foot of one of the three Graces (the one on the left). Finally, precisely because of its link with marriage and therefore with love, hyacinth could not fail to be represented before the figure of Venus, in the centre of the picture.

Alongside the hyacinths, there is also the plant traditionally mostly linked to the celebration of love: rose.

Rose

If the hypothesis that the Primavera painted by Botticelli was a wedding gift remains valid, the considerable representation of rose that would be found it’s not so surprising. However, although rose is by popularity the flower of love par excellence, very few people know the literary sources in which this connection is described.

Thanks to the sources carefully quoted by Mirella Levi d’Ancona in an essay – a text to which I have made great reference for this post –, it is possible to see how, since ancient times, rose was considered the queen of flowers: the flowers of this plant were used to make crowns and it was the favorite flower of poets and at the banquets as well.

Rose is also a symbol of pride and triumphant love: according to tradition, it would have been the flower brought by Venus when the goddess won the contest with the other goddesses in what is called the judgment of Paris.

The link with Venus, which is repeated in different sources , is expressed in the Uffizi’s Primavera by the plant represented right in the meadow space before the goddess of love.

An interesting quote about Rose comes from Poliziano himself who, in one of his Ballads, speaks about an”apron” and a “womb full of roses”, an image that immediately evokes the apron painted by Botticelli from which Flora sprinkles flowers on the lawn.

In another passage of the Stanze, the Tuscan poet defines Rose as “more daring” than the humble violet.

Detail of the plants in the lawn before the figure pf Chloris. Among the species: Cornflower, Iris and Violet have been here recognised

And it is with the latter plant that I conclude this brief excursus in search of some of the many plant species present in the Primavera painted by Botticelli.

Violet

Violet also is a plant linked to Venus as it is both a gift of love and a Chloris’ plant according to Poliziano; the poet also writes that it is by this flower that the Graces covered their breasts: thanks to violet, by which the Graces are dressed, the garden of the Hesperides – where these figures are doing their dance – is a more pleasant and more resplendent place.

Details of citruses trees, with fruits and orange-blossom, on the top of Primavera‘s painting

The last passage by Poliziano is very suggestive because it seems to have been reproduced almost literally in the Florentine painting: if someone looks at the top of the scene, it can be noticed many citrus fruits that look like the apples of the Hesperides. Taking into account all the literary references that have been found so far, is it possible that, making this painting, Botticelli meant to refer to the Garden of the Hesperides?

The many secrets and symbolic references of this extraordinary work of art will be uncovered by a guided tour in the Uffizi Gallery, a treasure chest literally full of treasures to discover ⟣

Bibliography:

– Mirella Levi D’Ancona, Botticelli’s primavera: a botanical interpretation including astrology, alchemy and the Medici with the first color reproductions of the Primavera since its restoration, Firenze, Olschki, 1983;

Webliography:

Letteritalia (consulted the 6th of February 2020)

Notes

1: B.da Sassoferrato, Ballate apocrife, XXXIV, p. 101;

2: G.Pontano, De Amore coniugali, Libro I e III of the Carmen nuptiale, line 14;

3: T.Tasso, Rime, 5 vol., Pisa 1891, vol. IV, part I, p.74;

4: It is said that a soft rose bush emerged when Venus emerged from the sea and a nectar caused the bush to become fully bloomed, Anacreon, Odes, 51;