Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi, 1504, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

The Dürer’s Uffizi painting at the Albertina in Vienna

Still impressed by the many works of art and the refined architecture seen on a trip to Vienna that I made early in 2020, now that I am back in my beautiful Tuscany, it comes back to my mind the Albrecht Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi, an unacknowledged masterpiece preserved in the Uffizi Gallery and which, to my surprise, I found in Vienna in the Albertina Museum on the occasion of an exhibition dedicated to the great German artist.

In the showcasing where the painting was located there was the opportunity to compare drawings, engravings – some already belonging to the museum’s permanent collection –, watercolours and paintings by the great artist from Nuremberg. The Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi appeared to me to be well highlighted in the Viennese exhibition – certainly also thanks to an adequate set-up in which, unfortunately, one still has no way of seeing when the work is in Florence – and placed side by side with other important and famous works by Dürer. The work is an oil on panel, measuring 99X113.5 cm and was created by Dürer in 1504 for Frederick the Wise, prince-elector of Saxony who wanted it for the chapel of the Castle of Wittenberg – a castle that the prince had rebuilt the year Before. In the 1600s the painting became part of the imperial collections of Rudolf II and was brought from Wittenberg to Vienna.

The setting of this Adoration of the Magi by Dürer is outdoors; in a space between ancient ruins which are rendered by the painter through the representation of massive arches, the madonna is placed on the left, represented in profile while she holds the baby Jesus, offering him towards the three kings who are about to adore him. Both the Virgin and the Magi stand on the steps of what appears to be an ancient temple. The oriental kings occupy a large part of the staircase and are represented of three different ages, according to a tradition that was now consolidated in art: one young, one adult and one elderly.

We therefore have the elderly Magus who is represented prostrate in front of the child, in the act of giving him a golden casket. Behind the old man we find the Magus in adulthood who holds in his right hand a precious pyx containing incense; his face is in profile, turned to our right, as if he were looking at the gift brought by the third king – the one with the most youthful features. The latter was also represented by Dürer both with a dark complexion and with a large earring hanging from his left ear, as if to emphasise his exotic origin. The gift he brings is myrrh, enclosed in a spherical pyx which is surmounted by a ouroboros.

Sacred Family with fragonfly, A.Dürer, 1495 c, Albertina, Vienna

Behind the beautiful profile of the Madonna in the foreground, we see the canonical representation of the ox and the donkey emerging from a wooden hut. Accompanying the group of three Magi is also a man of an equally exotic features, arranged at the foot of the staircase and who seems to be rummaging in a bag. The series of oriental characters ends with a group of men on horseback represented by the painter in the background space.

The scene is completed by the representation of a hill on which a castle stands out and, further to the left, a marine fragment can also be glimpsed.

The reason why this almost unknown work from the Uffizi can be ranked among Dürer’s masterpieces lies on the fact it is a painting in which the artist effectively combines elements of the Italian pictorial tradition together with others typical of the Northern European tradition.

Travels in Italy

Thanks to his travels in Italy, the Nuremberg artist was greatly fascinated by the Renaissance art of the peninsula. What interested Dürer a lot about the Italian manner was the arrangement of the figures in space perfected thanks to the rules of perspective, as well as the harmonious proportions of the human body studied by the great artists of the 15th century.

One of the elements that in this painting immediately refers us to the Italian tradition is that of the insertion of ruined architectures, a symbol of the end of paganism and the beginning of the Christian era.

Of this custom – by now consolidated in Italian painting of the 15th century – Dürer was certainly influenced by the vision of the painting of the peninsula, but it was probably the attendance of the workshops of Giovanni Bellini and Mantegna – the latter advocate of a taste for the ancient citation of purely “archaeological” character. The German master had his first direct contact with Venetian artists thanks to his first trip to Italy between 1494-95.

However, the ruins painted by Dürer are not the citation of the classical temple but are reworked in a more rustic way: instead of the classical friezes, in Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi we find the representation of squared stone boulders that appear rather rough, so much so that to be held together they need iron joints. The rustic aspect of this “old-fashioned” architecture is also highlighted by the wild vegetation that sprouts between the boulders which is where the painter invites us to linger with our gaze, given that the extremely detailed rendering of these elements is one of the technical qualities most notable of the painter.

His profound knowledge of plant species – as well as the faithful representation of some animal species – is one of the aspects highlighted by the curators of the Albertina exhibition; here, in fact, Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi is flanked both by watercolours with birds and rodents as subjects and by the famous engravings for the Apocalypse – which Dürer self-published in Nuremberg in 1494 – or by other stupendous compositions, such as the Holy Family with Dragonfly. This attention to detail becomes interesting in the Uffizi panel if we note that in the latter too we have the surprising presence of insects, as it can be seen on the stone boulders in the foreground, or the detailed representation of an ourobores on the pyx of the young Magus, symbols alluding to fascinating meanings that were common heritage among the Northern Europe people.

Detail of an illustration of the Apocalisse, A.Dürer, 1496-98, Albertina, Vienna

Great rendering of details

The rendering of these details is done with great skill by Dürer as well as the realisation of the landscape is carried out at high levels: the hill forming the background of the Adoration is surmounted by a castle building which, once again, recalls the Viennese engraving as it can be seen in one of the Apocalypse sheets with God enthroned and the four living beings.

It should be remembered the artist had acquired a great technical expertise for engravings thanks to the experience he gained as an illustrator, as for example in Basel, where, to get a job, he created the woodcuts for the Nave dei Folli, a publication in satirical character edited by the Dutchman Sebastian Brandt.¹

Returning to the Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi, a great attention to detail is demonstrated by Dürer in the characters clothes rendering, which refers to the lenticular rendering of Flemish painting, as can be seen in the Madonna who does not wear the classic Italian dress consisting of a cloak and but she has a garment almost looking like that of a maid. While this seems quite precious considering she is blue in colour, the white veil she has on her head represents the practical gesture of gathering and keeping her hair clean in housework. The Virgin is seated as she leans forward to bring the child closer to the kneeling Magus; however, it is not difficult to recognise in this figure the stature of a Northern European woman as she would be tall if she stood up. However, her body is not extremely slender but she seems to recall the fatigues of a body been dilated by the pregnancy now come to an end.

The elderly Magus wears a heavy red robe decorated with thick fur and prostrates before the infant Christ, a moment after having placed his sumptuous headdress on the stone boulder in the foreground. Behind him stands the imposing Magus in adulthood, characterised by Nordic features that some have wanted to recognise as those of Dürer himself. His clothing is equally sumptuous, as evidenced by the preciousness of his shiny green dress. The young Magus, on the other hand, wears more modest clothes, yet stands out thanks to his tights and the showy feathered hat held in his left hand.

Festa del Rosario, A.Dürer, 1506, Národní Galerie, Praga

Magi’s gifts featuring constitutes a supreme demonstration of Dürer’s technical ability. Starting from the golden casket of the elderly Magus to arrive at the pyx with the ouroboros of the young one, the yield of these artefacts is extraordinary which can also be explained thanks to the tradition of the artist’s family. In addition to the fact Dürer had great mastery of some goldsmith tools such as the burin and the punch – which he used for the matrices of his engravings –, both his brother and his father were established Nuremberg goldsmiths. Before Albrecht was born, his father – of Hungarian origin – had moved to the German city to work as a goldsmith.

The expertise shown by Dürer in this Uffizi Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi for the clothes rendering which, as it has been said, reflect Northern European fashion, is the demonstration of his profound knowledge and also of the attention he had shown in studying the great masters of Flemish-German area: for example, one of the personalities mostly observed is Martin Shongauer whose workshop Dürer visits, observing his drawings on a trip to Alsace.²

If so far we have had the opportunity to analyse some of the traits belonging to Dürer’s Nordic cultural background, now let’s see what elements of the Italian tradition emerge from the Uffizi Adoration.

Well, certainly the great chromatic liveliness of the painting cannot go unnoticed. The transparency of the colours in this work is somewhat reminiscent of watercolour — the latter technique used abundantly by the artist for preparatory studies or to immortalise the landscapes that inspired him during his travels. The tonal richness of the painting is an indication of the influence exerted on Dürer by Venetian painting which he was able to appreciate on his first trip to Italy.

Furthermore, on his second trip to the peninsula in 1506, the German artist had the opportunity to personally meet the young Titian who at the time was taking his first steps in the Venetian artistic environment. On that occasion, the master from Nuremberg created an important work which, together with the Adoration in the Uffizi, actually represents the artistic manifesto of his Italian influences: it is the so-called Feast of the Rosary, a majestic panel in the Národní Galerie in Prague and also present in the Albertina exhibition in Vienna.

Detail of men on horseback from the Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi, 1504, Uffizi

Detail of the Adoration of the Magi, L. da Vinci, 1481-82, Uffizi Gallery

The painting in the Uffizi is seen as purely dominated by warm colours in the foreground, where the ocher of the stone of the buildings prevails above all – and which becomes the ideal background to bring out the strong colours of the virgin dress and those of the Magi in the lower part, as well as the saturated colours of the sky in the upper part. Instead, what is seen in the background are the cold colours of the sky, at the same way for the castle and the sea. The white veil of the virgin is what in the foreground helps to guide the observer’s eye, allowing her face to be immediately identified.

As if this were not enough, in addition to the chromatic richness, Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi is based on a skilful distribution of solids and voids, as can be seen from the series of breakthroughs between the arches and the hut which are alternated with full of massive walls, like the one completely filling the space behind the audult Magus. The lines of the architecture, as well as the precise disposition of the characters, create a series of triangular patterns giving balance and breadth to the scene.

The illustrious precedent

I conclude the description of this unacknowledged masterpiece of the Uffizi with the group of men on horseback represented by Dürer in the background. Although at first sight this may appear only as a mere expedient of the painter to fill the background space and enrich the scene, one cannot fail to appreciate the meticulous rendering of these figures. What is further interesting about this group is a free homage that Dürer pays to another Adoration of the Magi, also kept in the Uffizi: it is the one painted and never completed a few decades earlier by the great Leonardo da Vinci. It is not known for certain whether the German master was able to appreciate from live the Florentine altarpiece, but he certainly was able to study it through some engravings. The correspondence with Leonardo’s painting is appreciated, notably with the quotation of the man riding the runaway horse.

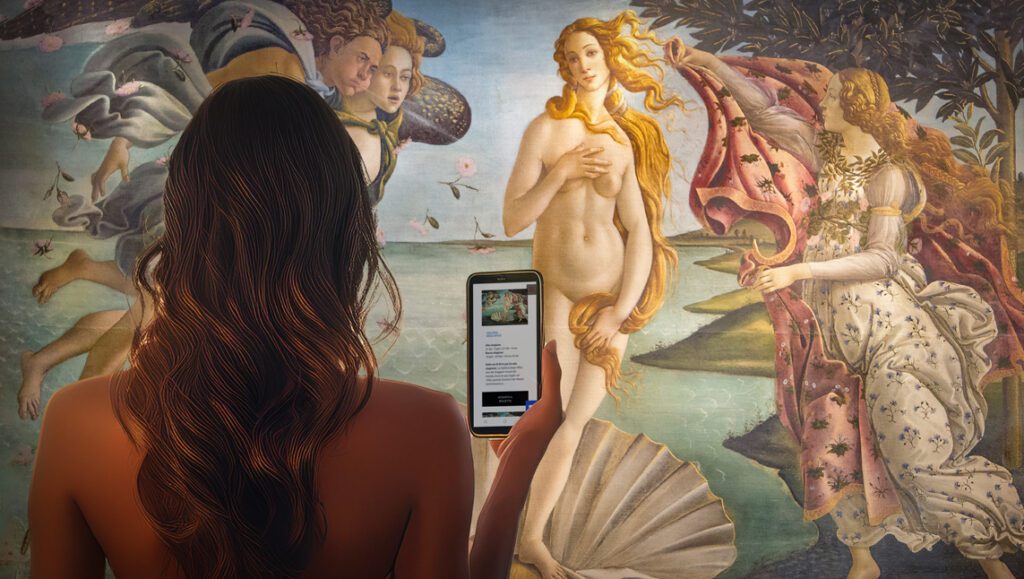

This analysis aims to make people understand how Dürer’s Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi is a work of equal importance to the masterpieces of Botticelli, Leonardo and Michelangelo. Seeing this work and admiring the series of details it contains is a great experience to discover a masterpiece by one of the greatest European artists.

However, it still remains to be discovered why this work, commissioned — as has been said — for the castle of Wittenberg, is now kept in the Uffizi; or, what is the symbology of the insects or of the ouroboros the artist features inside the painting? Dürer used to put his signature on the works through a very particular acronym that is easily identifiable in his engravings. Where is Dürer’s signature hiding in this Uffizi masterpiece? You can discover all these mysteries with a guided tour of the Uffizi Gallery ⟣

Bibliography

1: G.Bott (a cura di), La pittura in Europa. La pittura tedesca, Milano 1996 (Italian edition)

2: ibid

Webliography

1: Analisi dell’opera, consultato il 04/01/2020